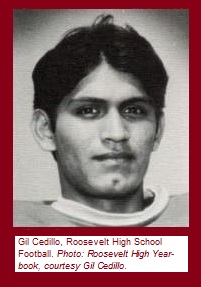

L.A. Councilmember Gil Cedillo, a Former Roosevelt Rough Rider Quarterback, Recalls the 1970 Chicano Moratorium

One Saturday morning in late August 50 years ago, I finished my household chores early and slipped out of the house to meet some friends. We were going to the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War. I was 16 years old, and this would be my first protest march. As it turned out, those were my first steps in a long march toward a more just world.

I played quarterback on Roosevelt High’s Rough Riders football team, which at the time was my main goal in life. That day I marched with Mario Chacón and some other friends my parents called greñudos–longhairs. An estimated 30,000 marchers made the Moratorium the largest political protest in Los Angeles history.

The Moratorium was a turning point for legions of young community activists. Marchers included political leaders Esteban Torres and Gloria Molina, attorneys Antonia Hernandez and Samuel Paz, photographer Luis Garza, and educator Maria Elena Yepes.

My greñudo friend Mario and I wound up being roommates later at UCLA. He became an academic leader and a recognized muralist in San Diego. I fought on in the labor movement and political arena.

The Moratorium, however, ended in mayhem. Sheriff Peter Pitchess’ deputies declared the speakers and music in Laguna Park an unlawful assembly and attacked families with tear gas and 3-foot riot clubs. I remember the mood turning from pride and festivity to hysteria in an instant, and thousands of unarmed demonstrators trying to get out of harm’s way.

I was an athlete, and it wasn’t hard for me to hop fences. I found shelter in a house nearby packed with frantic participants from the Crusade for Justice, the leading Chicano rights organization in Denver. When things settled down, I began working my way home. I was walking up Whittier Boulevard when the booming voice of my father, a Korean War veteran and former boxer, rang out: “Get in the car!” We argued all the way home. He grounded me.

Three people died in the Moratorium’s violent aftermath, but Ruben Salazar’s death has become almost synonymous with August 29. Salazar was news director for KMEX Channel 34, the country’s preeminent Spanish language TV station, and was leading a camera crew covering the march.

Salazar also wrote a weekly column on Mexican American life for the L.A. Times, where he had been a reporter and foreign correspondent. My sociology teacher used his best-known column–“Who Is a Chicano? An What Is It Chicanos Want?”–to spark class discussion.

That fall I began my junior year at Roosevelt. I still made the football team, but politics was now personal. I moved from individualism and assimilation to being part of a community. This new Chicano identity was bigger than me. It was a movement, and I made a commitment to fight for social justice that I have kept ever since.

Those sharp and vivid memories have inspired me every day for five decades. I can see the progress Latinos have made in every walk of life, but I also see inequality by so many yardsticks. Our communities suffer the highest COVID infection rate and the highest incarceration rate. And 7,000 immigrant children who were torn from their parents’ arms are still in detention.

|

Los Angeles City Council Member District 1 Gil Cedillo at the 50th Anniversary Commemoration of the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War held recently in East Los Angeles. |

Comments

Post a Comment