El Como y Porque de '43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson'

Organized as a collaboration between three well-known LA non-profit arts organizations that include socially and politically engaged art as an integral part of their focus, 43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson opened at Self Help Graphics & Art on May 12th. The milestone exhibition, an effort to underscore a parallel between the reasons for the rise of the #blacklivesmatter movement in the U.S. and the disappearance of 43 politically active students from La Escuela Normal Rural Raúl Isidro Burgos in Ayotzinapa, Mexico, featured work by artists from throughout the world.

“We wanted to bring artists from both the African-American and Chicano-Mexicano communities together over the idea that excessively aggressive policing in places like Ferguson, New York, Texas, the Bay Area, is part of a larger problem,” says co-curator Jimmy O’Balles.

Raised in both LA’s East Side and Monrovia before being sent to Vietnam, O’Balles founded the Monrovia Latino Heritage Society and has organized cultural events around African-American and Chicano unity for over two decades, including the Love, Revolution & the Black Panther Party exhibition held at ArtShare in Downtown LA in 2014.

The effort to link Ayotzinapa—where the final destiny of students last seen under custody of state police authorities may never be known—with the disproportionate deaths of Black youth in the U.S. at the hands of police, O’Balles explains, evolved from a conversation with artist Tito Delgado. A widely recognized artist who has designed, fabricated and installed large-scale public art projects across the U.S., Delgado had been part of a homage to late Congressman Edward Roybal curated by O’Balles at Align Gallery, co-owned by Roybal’s granddaughter, Loushana Roybal Rose.

While organizing the Roybal show, O’Balles sought out Abel Salas, a co-founder of and primary curator at Corazon del Pueblo, an all-volunteer neighborhood cultural center that grew out of a storefront in Boyle Heights established earlier by Salas as a literary and visual arts venue with support from playwright Josefina López, artistic director and founder of Casa 0101, a neighboring black box theater.

“I’d been hearing about Corazón del Pueblo and this newspaper dude for years,” O’Balles says of the outspoken journalist and arts advocate. “But he was like a ghost. Friends in Leimert Park, Chicano artists, folks on the west side, in the Bay Area and even outside of California were all hip to him, but no one knew where to find him.” O’Balles recalls. “I finally found him camped out in a warehouse near Hazard Park.”

“Jimmy’s a Vietnam vet and a visionary. He bridges communities through art. And he has soul,” says Salas, who readily volunteered for the Roybal exhibit. Not long after, O’Balles, Delgado and Salas fell in for a Saturday night art crawl with O’Balles behind the wheel.

“When we got to Tito’s, I gave up shotgun and hopped in back out of respect,” says Salas. “I asked about his studio in Chiapas and told him about my journey there in January of ’94 right after the Zapatista uprising,” says Salas. “He reached back and handed me a ceramic tile imprinted with the number 43 and silhouetted images, one of many he'd produced. It had been a year since the kids in Ayotzinapa had gone missing.”

Salas recounted for his newly adopted honorary older brothers his brief march alongside over 100,000 protestors in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico in late October just as news of the brutal police assault was unfolding.

Salas recounted for his newly adopted honorary older brothers his brief march alongside over 100,000 protestors in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico in late October just as news of the brutal police assault was unfolding.

“I had just been part of a poetry festival in Ajalpan, Puebla. From there, a group us headed to D.F. to read at the Proyecto Sur international art summit,” Salas explains. The garrita, or toll station on the highway out of Puebla, Salas recalled for Delgado and O’Balles from the back seat, had been taken over by student demonstrators from the Escuela Normal de Puebla, a sister university to the one in Ayotzinapa, who asked drivers not to pay the toll as a gesture of protest.

“In Mexico City, the streets were packed with thousands and thousands of students headed downtown. We had to park and take the Metro,” Salas informed them. “Even so, it took over an hour and two separate trains to get to the center of the city.”

From the driver’s seat, O’Balles responded with memories of the Black Panther and the Chicano movements a generation before that had inspired him upon his return from Vietnam and had led to the Black Panther exhibition he’d organized the summer before, two months prior to the attack on innocent, unarmed youth from the school in Ayotzinapa.

Making a final stop for loaded fries, chili and drinks at a place on Figueroa in Highland Park en route to Delgado’s home as their evening drew to a close, the artist mulled over the earlier conversations and offered a provocative thought, one Salas and O’Balles knew they needed to run with.

“I just told Jimmy and Abel that I thought it would be pretty cool if they could put together a show that drew a connection between Black Lives Matter and what had happened in Ayotzinapa. I knew some activists in Mexico were already making that association,” says Delgado. “But nobody here had picked up on it outside of protests.”

At a Self Help opening shortly afterward, O’Balles and Salas each arrived independently at the conclusion that the converted warehouse at 1st St. and Anderson would be ideal. Betty Avila and Joel García, co-directors hired as part of a new horizontal management structure meant to revitalize the venerable East Side arts institution, responded positively to the idea and tentatively agreed to host the exhibition.

43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson went, at that moment, from standby status as an impassioned proposal to a tangible reality. García, with deep roots on the East Side as an artist and a cultural activist, wisely suggested enlisting master printmaker Daniel González. An artist whose satirical, occasionally whimsical and always complex work consistently reflects a profound sense of social responsibility, González is a Boyle Heights native with family roots in Zacatecas. His woodcuts, linocuts and etchings follow in the populist tradition of Mexican printer and engraver José Guadalupe Posada as well as that of printmaker Leopoldo Méndez, founder of the Taller de Gráfica Popular.

Moved by the Ayotzinapa tragedy, González became involved with efforts propelling the “re-animation” of El Ahuizote, a liberal Mexico City newspaper established in 1885. Licensed in 1902 to brothers Ricardo Flores Magón and Enrique Flores Magón, publishers of the more radical Regeneración, El Ahuizote folded when the Flores Magón brothers were driven out of the building that housed their offices and presses for their opposition to the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship. They later left Mexico as exiles.

Diego Flores Magón, great-grandson of Enrique Flores Magón, successfully petitioned for permission to develop an archival museum on the upper floors of the building once known as “La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote.”

González joined artists and writers from the U.S. for an “impromptu action” in solidarity with those in Mexico taking on state violence, as contributors to a series of new El Ahuizote broadsides distributed for free at major protest marches and demonstrations in Mexico on Dec. 1st and Dec. 6th of 2014.

In keeping with its original mission to train artists in printmaking techniques, Self Help also hosted a print atelier for artists interested in creating works on paper for inclusion in the exhibit which produced an array of strikingly relevant images based on the exhibition title and conceptual framework.

The project was also marked by a unique partnership with Venice-based Social & Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) and LA’s Center for the Study of Political Graphics. Facilitated by SPARC curator Marietta Bernstorff, a stand-alone exhibition of 43 posters—culled from 700 design submissions sent to renowned artist Francisco Toledo and the Instituto de Artes Gráficas de Oaxaca—was made available to augment the selection of locally produced paintings, photographs prints and mixed media works submitted through the initial curatorial overtures.

Billed as Ayotzinapa: A Roar of Silence, the poster art was a response to Ayotzinapa and came after a world-wide call for entries issued by Toledo, whose installation piece—comprised of 43 small white kites, each bearing a photo of a missing student—accompanied the poster collection. Hung from the ceiling at SHG, the kites imbued the entire exhibition with an eerie resonance. Under their ghostly sway, the exhibition was layered with a reverence for the sanctity of life.

According to several artists who took part in the groundbreaking exhibition, there is interest from outside of Los Angeles in a reprisal of the show. “I would rather not mention the possible travel of the exhibition. Don't wanna jinx it,” wrote Self Help’s Joel García in response to an email query.

In the end, says James “Jimmy” O’Balles, the exhibit conceived in his car and bearing a title offered by co-curator Salas, was and remains a visual prayer for peace, tolerance and healing.

“It’s a protest song composed of all the images and works of art in honor of those on both sides of the border who didn’t deserve to die and aren’t here to tell us what really happened,” he adds solemnly.

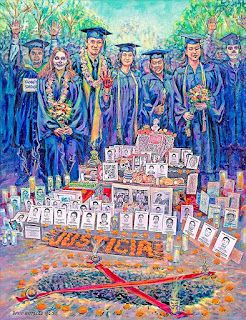

Art from top: David Botello, Justice for the 43, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas; Joel García, 43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson, 2016, Graphic flyer/post card design; Sergio Arau, Ayotzinapa-Ferguson: Sister Cities, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas

“We wanted to bring artists from both the African-American and Chicano-Mexicano communities together over the idea that excessively aggressive policing in places like Ferguson, New York, Texas, the Bay Area, is part of a larger problem,” says co-curator Jimmy O’Balles.

Raised in both LA’s East Side and Monrovia before being sent to Vietnam, O’Balles founded the Monrovia Latino Heritage Society and has organized cultural events around African-American and Chicano unity for over two decades, including the Love, Revolution & the Black Panther Party exhibition held at ArtShare in Downtown LA in 2014.

The effort to link Ayotzinapa—where the final destiny of students last seen under custody of state police authorities may never be known—with the disproportionate deaths of Black youth in the U.S. at the hands of police, O’Balles explains, evolved from a conversation with artist Tito Delgado. A widely recognized artist who has designed, fabricated and installed large-scale public art projects across the U.S., Delgado had been part of a homage to late Congressman Edward Roybal curated by O’Balles at Align Gallery, co-owned by Roybal’s granddaughter, Loushana Roybal Rose.

“I’d been hearing about Corazón del Pueblo and this newspaper dude for years,” O’Balles says of the outspoken journalist and arts advocate. “But he was like a ghost. Friends in Leimert Park, Chicano artists, folks on the west side, in the Bay Area and even outside of California were all hip to him, but no one knew where to find him.” O’Balles recalls. “I finally found him camped out in a warehouse near Hazard Park.”

“Jimmy’s a Vietnam vet and a visionary. He bridges communities through art. And he has soul,” says Salas, who readily volunteered for the Roybal exhibit. Not long after, O’Balles, Delgado and Salas fell in for a Saturday night art crawl with O’Balles behind the wheel.

“When we got to Tito’s, I gave up shotgun and hopped in back out of respect,” says Salas. “I asked about his studio in Chiapas and told him about my journey there in January of ’94 right after the Zapatista uprising,” says Salas. “He reached back and handed me a ceramic tile imprinted with the number 43 and silhouetted images, one of many he'd produced. It had been a year since the kids in Ayotzinapa had gone missing.”

Salas recounted for his newly adopted honorary older brothers his brief march alongside over 100,000 protestors in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico in late October just as news of the brutal police assault was unfolding.

Salas recounted for his newly adopted honorary older brothers his brief march alongside over 100,000 protestors in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico in late October just as news of the brutal police assault was unfolding.“I had just been part of a poetry festival in Ajalpan, Puebla. From there, a group us headed to D.F. to read at the Proyecto Sur international art summit,” Salas explains. The garrita, or toll station on the highway out of Puebla, Salas recalled for Delgado and O’Balles from the back seat, had been taken over by student demonstrators from the Escuela Normal de Puebla, a sister university to the one in Ayotzinapa, who asked drivers not to pay the toll as a gesture of protest.

“In Mexico City, the streets were packed with thousands and thousands of students headed downtown. We had to park and take the Metro,” Salas informed them. “Even so, it took over an hour and two separate trains to get to the center of the city.”

From the driver’s seat, O’Balles responded with memories of the Black Panther and the Chicano movements a generation before that had inspired him upon his return from Vietnam and had led to the Black Panther exhibition he’d organized the summer before, two months prior to the attack on innocent, unarmed youth from the school in Ayotzinapa.

Making a final stop for loaded fries, chili and drinks at a place on Figueroa in Highland Park en route to Delgado’s home as their evening drew to a close, the artist mulled over the earlier conversations and offered a provocative thought, one Salas and O’Balles knew they needed to run with.

“I just told Jimmy and Abel that I thought it would be pretty cool if they could put together a show that drew a connection between Black Lives Matter and what had happened in Ayotzinapa. I knew some activists in Mexico were already making that association,” says Delgado. “But nobody here had picked up on it outside of protests.”

Relying on phone calls and texts, O’Balles pitched the exhibit idea to all of those who had shown at the Align Gallery, a core of LA’s most accomplished and well-known Chicana and Chicano artists who agreed to participate in a still untitled and technically homeless exhibition, without hesitation. O’Balles tackled the venue issue and approached two separate art spaces and was told the concept was too controversial.

At a Self Help opening shortly afterward, O’Balles and Salas each arrived independently at the conclusion that the converted warehouse at 1st St. and Anderson would be ideal. Betty Avila and Joel García, co-directors hired as part of a new horizontal management structure meant to revitalize the venerable East Side arts institution, responded positively to the idea and tentatively agreed to host the exhibition.

43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson went, at that moment, from standby status as an impassioned proposal to a tangible reality. García, with deep roots on the East Side as an artist and a cultural activist, wisely suggested enlisting master printmaker Daniel González. An artist whose satirical, occasionally whimsical and always complex work consistently reflects a profound sense of social responsibility, González is a Boyle Heights native with family roots in Zacatecas. His woodcuts, linocuts and etchings follow in the populist tradition of Mexican printer and engraver José Guadalupe Posada as well as that of printmaker Leopoldo Méndez, founder of the Taller de Gráfica Popular.

Moved by the Ayotzinapa tragedy, González became involved with efforts propelling the “re-animation” of El Ahuizote, a liberal Mexico City newspaper established in 1885. Licensed in 1902 to brothers Ricardo Flores Magón and Enrique Flores Magón, publishers of the more radical Regeneración, El Ahuizote folded when the Flores Magón brothers were driven out of the building that housed their offices and presses for their opposition to the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship. They later left Mexico as exiles.

Diego Flores Magón, great-grandson of Enrique Flores Magón, successfully petitioned for permission to develop an archival museum on the upper floors of the building once known as “La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote.”

González joined artists and writers from the U.S. for an “impromptu action” in solidarity with those in Mexico taking on state violence, as contributors to a series of new El Ahuizote broadsides distributed for free at major protest marches and demonstrations in Mexico on Dec. 1st and Dec. 6th of 2014.

In keeping with its original mission to train artists in printmaking techniques, Self Help also hosted a print atelier for artists interested in creating works on paper for inclusion in the exhibit which produced an array of strikingly relevant images based on the exhibition title and conceptual framework.

The project was also marked by a unique partnership with Venice-based Social & Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) and LA’s Center for the Study of Political Graphics. Facilitated by SPARC curator Marietta Bernstorff, a stand-alone exhibition of 43 posters—culled from 700 design submissions sent to renowned artist Francisco Toledo and the Instituto de Artes Gráficas de Oaxaca—was made available to augment the selection of locally produced paintings, photographs prints and mixed media works submitted through the initial curatorial overtures.

Billed as Ayotzinapa: A Roar of Silence, the poster art was a response to Ayotzinapa and came after a world-wide call for entries issued by Toledo, whose installation piece—comprised of 43 small white kites, each bearing a photo of a missing student—accompanied the poster collection. Hung from the ceiling at SHG, the kites imbued the entire exhibition with an eerie resonance. Under their ghostly sway, the exhibition was layered with a reverence for the sanctity of life.

According to several artists who took part in the groundbreaking exhibition, there is interest from outside of Los Angeles in a reprisal of the show. “I would rather not mention the possible travel of the exhibition. Don't wanna jinx it,” wrote Self Help’s Joel García in response to an email query.

In the end, says James “Jimmy” O’Balles, the exhibit conceived in his car and bearing a title offered by co-curator Salas, was and remains a visual prayer for peace, tolerance and healing.

“It’s a protest song composed of all the images and works of art in honor of those on both sides of the border who didn’t deserve to die and aren’t here to tell us what really happened,” he adds solemnly.

Art from top: David Botello, Justice for the 43, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas; Joel García, 43: From Ayotzinapa to Ferguson, 2016, Graphic flyer/post card design; Sergio Arau, Ayotzinapa-Ferguson: Sister Cities, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas

Comments

Post a Comment