Reluctant Ex-patriot or Undocumented Immigrant?

Part One

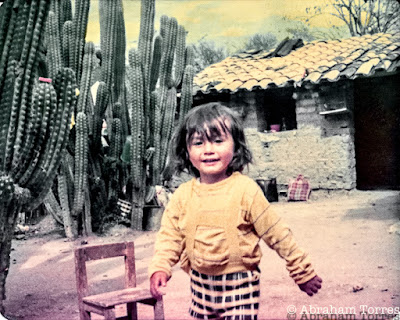

by Abraham Torres

Mom: You want me to go where? No. No. No. I am very happy here, and I don’t know why YOU want to go. WE have a good life here. YOU have a good life here! Are you crazy? He’s only two years old! We can’t travel, much less live in another country. We have no good reason to go. Maybe when he gets a little older, but not now, it’s a not a good time.

Mom: (Several weeks later) I said, No! Look at you, you’ve been there a week and been caught three times. You think I’m going to share your experience with a two-year-old in my arms? I don’t care if you’ve been “told” it’s great over there and worth the effort. I know you think we’ll have a better life, a better life than you had growing up after your father was killed in a gunfight, a better life for our son, a better life for me. I know you think I’ll like it there, and we can be more secure because we’ll be making much more money than what your current job is giving you, but I don’t care. We’ll make it here just the same...you don’t even know English!

Mom: (Over the phone, later) I’m glad you found a job and are making good money. I don’t want to go.

Mom: (Over the phone) Why did you send plane tickets? I said No. We are not going!!!

Aeroméxico Flight Attendant: (In Spanish) Please make sure your folding trays and seats are in their full upright position. Please fasten your seat belts as we prepare for landing in Baja, California, and welcome to Tijuana, Mexico.

Mom: (Thinking to herself) I don’t know why I’m here. I never even applied for a passport. All I have is our birth certificates. I told him I didn’t want to come. This trip is going to end before it even begins.

Tijuana International Airport PA System: Please have your documents ready for inspection.

Meanwhile, almost as if by fate, a blonde-haired gentleman is fumbling through his documents, while wrangling his trail of luggage. My mom happens to be standing next to him, and by chance, my toddler hair is still a wispy blonde, so the airport official motions my mom to step forward and pass on through, as my mom’s implied “husband” and, by extension, my “father,” clumsily gets his paperwork together. My mom passes through, holding me in her arms, hails a taxi, and we head off to our hotel without the fair-skinned unwitting accessory to our trouble-free arrival in TJ.

Mom: (Thinking to herself in the hotel) I don’t want to be here. What am I doing in this place? It is dirty and ugly. I want to go home. I can’t believe I made it past the airport security station. But we will not cross the border, we won’t have such luck. (Looking at me) “We’ll be going home soon.”

(A knock at the door.)

Mom: Ah, Tío Rubén, hello.

My Uncle Rubén encounters two reluctant and beleaguered travelers. This isn’t his first time, so he doesn’t ask my mom for any documents.

Tío Rubén: How was your flight? Do you like your hotel room?

Mom: (Sighing at his rhetorical questions) When are we leaving?

Tio Rubén: Right now. Get your things. We don’t have time to waste.

Night has fallen, we jump into a van, and drive off to “The Line,” but my uncle knows of a smaller crossing and heads off to the Otay Mesa Port of Entry.

Tío Ruben: Now, don’t say a word, and have Abran stay as quite as possible. You are my wife, and he is my son. (We arrive at the crossing, and my mom really begins to wonder why Tío Rubén hasn’t asked for her passport, much less our birth certificates. Light from the hanging florescent tubes in the border crossing checkpoint creep into our van as we slow to a complete stop and Uncle Rubén turns the engine off.)

Border Agent: Good evening. Papers, please.

Tío Ruben hands the border agent what seems to be a passport and declares us his wife and child. My mom says nothing, but is quietly confused. The agent glances at my mom and me. We glance back, say nothing. Looking back down at the paperwork again, and back at the family unit, he finally says...

Border Agent: Okay, move along. And welcome to the United States. (My mother was stunned, she had tried everything in her power to go home. Nothing had worked, and now, instead of returning to Puebla, she and I were on our way to join my father and begin our first international adventure. Fate, it seems, had other plans.)

This is the story as told to me by my parents, who recently began sharing their adventures, through interviews I initiated. Why did you choose LA? Was it because of Hollywood? Were you lured by Americana? Why come to the US when you already had a job in Puebla? What was your impression when you first saw the Pacific Ocean? Why did you become an American Citizen? Was it easy learning English?

These are just some of the questions I put forth as a way to approach a retrospective of my childhood experience and the reason I grew up as an adopted child of Los Angeles. Somewhere inside my psyche, it had become apparent that there was something missing, a void, a longing, a yearning to look back my journey and ask why it happened in the first place.

As a child, I did not comprehend why LAX was a constantly recurring site, why Mexico City International Airport reintroduced me every so often to forgotten aromas, why the Puebla bus terminal had become a fixture in my mind, why I always had to say goodbye to a multitude of cousins, aunts, uncles.

My mother is one of eight brothers and nine sisters. One of my aunts has 18 children, anyone of whom I had either just met, reconnected with, played with, ate with, laughed with or wondered about quizzically when they did not join us on our return flight to the U.S. At the time, the sporadic effect of extended family vs. location did not seem to be a big deal, but as I grew up and became a man, I began to remember the loneliness I had experienced as a child and how distance and the random access to an extended family affected me.

It may very well be the reason I became shy, hiding from the pretty lady instructor behind my mom on the first day of pre-school. It may have protracted my feelings of isolation. It might be why I was drawn to subjects where I could pull away, hide, create my own worlds, classes like science, writing, photography.

I remember telling my mom, I wanted to be a Park Ranger when I grew up, so I could be with and protect the forest. Wearing eyeglasses did not help the situation, nor did only possessing a green card as opposed to being a fully-fledged citizens. We were living in another country, with yes, familiar attributes of home, but nonetheless felt isolated in comparison to the large family we had just left.

Based on all this, I’ve recently recognized a need to reclassify my designation. I am less a Mexican-American living in Los Angeles and more a Mexican National, who hitched a ride in on his mom’s lap to live in the United States,. I was, to borrow a song title from Sting, the equivalent of an ‘Englishmen [living] New York,’ an expatriate, “one who withdraws (oneself) from residence in one’s native country.” And this experience is very unique to expatriates. Just ask any kid of a diplomat stationed in a foreign office or an army brat.

Now, I understand I had little choice. My “input” in the matter at two-years-old was slim at best, but as I grew into my newfound city, its culture, its people, I began to realize the amazing impact my father’s dreams and desires have had on my life. The immediate goal of providing a better life for my mom and me had a real impact that brought on—of course—pain, sadness and loneliness. Yet it also presented a previously unimaginable world of energy, life and experiences that I don’t have the words to describe, but will try to nonetheless.

My father never wanted to depend on a handout. Nor would he have ever allowed himself to beg. He was looking for work that would earn us a living wage. Mexico was not providing this. By taking a leap of faith, he forged an opening and created a path for our family to improve its circumstances. He created his own luck, and—in turn —created the conditions whereby we could gain a firm foothold, a beachhead, on foreign land.

The heroic, ballsy decision to get up and jump, to find the confidence to make it happen, to figure it out, one way or another, English or no English, formal education or not, connections or no connections, family name or no family name, created an opportunity. And hard work was the only constant my parents could bank on.

Next month: Ex-pat or Immigrant Part 2

by Abraham Torres

Mom: You want me to go where? No. No. No. I am very happy here, and I don’t know why YOU want to go. WE have a good life here. YOU have a good life here! Are you crazy? He’s only two years old! We can’t travel, much less live in another country. We have no good reason to go. Maybe when he gets a little older, but not now, it’s a not a good time.

Mom: (Several weeks later) I said, No! Look at you, you’ve been there a week and been caught three times. You think I’m going to share your experience with a two-year-old in my arms? I don’t care if you’ve been “told” it’s great over there and worth the effort. I know you think we’ll have a better life, a better life than you had growing up after your father was killed in a gunfight, a better life for our son, a better life for me. I know you think I’ll like it there, and we can be more secure because we’ll be making much more money than what your current job is giving you, but I don’t care. We’ll make it here just the same...you don’t even know English!

Mom: (Over the phone, later) I’m glad you found a job and are making good money. I don’t want to go.

Mom: (Over the phone) Why did you send plane tickets? I said No. We are not going!!!

Aeroméxico Flight Attendant: (In Spanish) Please make sure your folding trays and seats are in their full upright position. Please fasten your seat belts as we prepare for landing in Baja, California, and welcome to Tijuana, Mexico.

Mom: (Thinking to herself) I don’t know why I’m here. I never even applied for a passport. All I have is our birth certificates. I told him I didn’t want to come. This trip is going to end before it even begins.

Tijuana International Airport PA System: Please have your documents ready for inspection.

Meanwhile, almost as if by fate, a blonde-haired gentleman is fumbling through his documents, while wrangling his trail of luggage. My mom happens to be standing next to him, and by chance, my toddler hair is still a wispy blonde, so the airport official motions my mom to step forward and pass on through, as my mom’s implied “husband” and, by extension, my “father,” clumsily gets his paperwork together. My mom passes through, holding me in her arms, hails a taxi, and we head off to our hotel without the fair-skinned unwitting accessory to our trouble-free arrival in TJ.

Mom: (Thinking to herself in the hotel) I don’t want to be here. What am I doing in this place? It is dirty and ugly. I want to go home. I can’t believe I made it past the airport security station. But we will not cross the border, we won’t have such luck. (Looking at me) “We’ll be going home soon.”

(A knock at the door.)

Mom: Ah, Tío Rubén, hello.

My Uncle Rubén encounters two reluctant and beleaguered travelers. This isn’t his first time, so he doesn’t ask my mom for any documents.

Tío Rubén: How was your flight? Do you like your hotel room?

Mom: (Sighing at his rhetorical questions) When are we leaving?

Tio Rubén: Right now. Get your things. We don’t have time to waste.

Night has fallen, we jump into a van, and drive off to “The Line,” but my uncle knows of a smaller crossing and heads off to the Otay Mesa Port of Entry.

Tío Ruben: Now, don’t say a word, and have Abran stay as quite as possible. You are my wife, and he is my son. (We arrive at the crossing, and my mom really begins to wonder why Tío Rubén hasn’t asked for her passport, much less our birth certificates. Light from the hanging florescent tubes in the border crossing checkpoint creep into our van as we slow to a complete stop and Uncle Rubén turns the engine off.)

Border Agent: Good evening. Papers, please.

Tío Ruben hands the border agent what seems to be a passport and declares us his wife and child. My mom says nothing, but is quietly confused. The agent glances at my mom and me. We glance back, say nothing. Looking back down at the paperwork again, and back at the family unit, he finally says...

Border Agent: Okay, move along. And welcome to the United States. (My mother was stunned, she had tried everything in her power to go home. Nothing had worked, and now, instead of returning to Puebla, she and I were on our way to join my father and begin our first international adventure. Fate, it seems, had other plans.)

This is the story as told to me by my parents, who recently began sharing their adventures, through interviews I initiated. Why did you choose LA? Was it because of Hollywood? Were you lured by Americana? Why come to the US when you already had a job in Puebla? What was your impression when you first saw the Pacific Ocean? Why did you become an American Citizen? Was it easy learning English?

These are just some of the questions I put forth as a way to approach a retrospective of my childhood experience and the reason I grew up as an adopted child of Los Angeles. Somewhere inside my psyche, it had become apparent that there was something missing, a void, a longing, a yearning to look back my journey and ask why it happened in the first place.

As a child, I did not comprehend why LAX was a constantly recurring site, why Mexico City International Airport reintroduced me every so often to forgotten aromas, why the Puebla bus terminal had become a fixture in my mind, why I always had to say goodbye to a multitude of cousins, aunts, uncles.

My mother is one of eight brothers and nine sisters. One of my aunts has 18 children, anyone of whom I had either just met, reconnected with, played with, ate with, laughed with or wondered about quizzically when they did not join us on our return flight to the U.S. At the time, the sporadic effect of extended family vs. location did not seem to be a big deal, but as I grew up and became a man, I began to remember the loneliness I had experienced as a child and how distance and the random access to an extended family affected me.

It may very well be the reason I became shy, hiding from the pretty lady instructor behind my mom on the first day of pre-school. It may have protracted my feelings of isolation. It might be why I was drawn to subjects where I could pull away, hide, create my own worlds, classes like science, writing, photography.

I remember telling my mom, I wanted to be a Park Ranger when I grew up, so I could be with and protect the forest. Wearing eyeglasses did not help the situation, nor did only possessing a green card as opposed to being a fully-fledged citizens. We were living in another country, with yes, familiar attributes of home, but nonetheless felt isolated in comparison to the large family we had just left.

Based on all this, I’ve recently recognized a need to reclassify my designation. I am less a Mexican-American living in Los Angeles and more a Mexican National, who hitched a ride in on his mom’s lap to live in the United States,. I was, to borrow a song title from Sting, the equivalent of an ‘Englishmen [living] New York,’ an expatriate, “one who withdraws (oneself) from residence in one’s native country.” And this experience is very unique to expatriates. Just ask any kid of a diplomat stationed in a foreign office or an army brat.

Now, I understand I had little choice. My “input” in the matter at two-years-old was slim at best, but as I grew into my newfound city, its culture, its people, I began to realize the amazing impact my father’s dreams and desires have had on my life. The immediate goal of providing a better life for my mom and me had a real impact that brought on—of course—pain, sadness and loneliness. Yet it also presented a previously unimaginable world of energy, life and experiences that I don’t have the words to describe, but will try to nonetheless.

My father never wanted to depend on a handout. Nor would he have ever allowed himself to beg. He was looking for work that would earn us a living wage. Mexico was not providing this. By taking a leap of faith, he forged an opening and created a path for our family to improve its circumstances. He created his own luck, and—in turn —created the conditions whereby we could gain a firm foothold, a beachhead, on foreign land.

The heroic, ballsy decision to get up and jump, to find the confidence to make it happen, to figure it out, one way or another, English or no English, formal education or not, connections or no connections, family name or no family name, created an opportunity. And hard work was the only constant my parents could bank on.

Next month: Ex-pat or Immigrant Part 2

Comments

Post a Comment