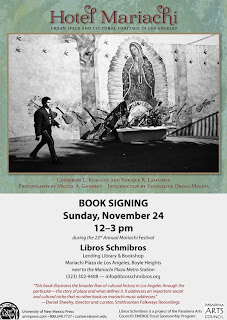

HOTEL MARIACHI Booksigning!

Join us this Sunday for a HOTEL MARIACH: Urban Space and Cultural Heritage in Los Angeles book signing with the authors. The event will be held at Libros Schmibros from 12 - 3pm on Mariachi Plaza during the 23rd Annual Mariachi Festival in Boyle Heights. We hope to see you there. Pick up your latest edition of Brooklyn & Boyle while you're there. Here's the review I've written.

Join us this Sunday for a HOTEL MARIACH: Urban Space and Cultural Heritage in Los Angeles book signing with the authors. The event will be held at Libros Schmibros from 12 - 3pm on Mariachi Plaza during the 23rd Annual Mariachi Festival in Boyle Heights. We hope to see you there. Pick up your latest edition of Brooklyn & Boyle while you're there. Here's the review I've written.-----------------------

Hotel Mariachi: Urban Space and Cultural Heritage in Los Angeles is a book that operates in a critical and pivotal nexus. It could not be more necessary, urgent, timely or beautiful if it tried. At once scholarly and a divinely inspired treatise on the art and culture of mariachi, the book is also a love letter to the ghosts of mariachi music and the city of Los Angeles, historic Boyle Heights and those itinerant musicians who have yet to arrive.

Part family history, part literary and photo-documentary as well as a sterling work of ethno-musicology, Hotel Mariachi brings together the family memoir, a glittering portfolio of photographs in homage to the humble musicians who have plied their trade from the famed Mariachi Plaza for over half a century and a serious, in-depth study of mariachi as a musical form unto itself through a look at the annual celebration in honor of every musician’s patron saint, Santa Cecilia.

As important as all those elements are, they could not have coalesced without Kurland’s love for architecture and the efforts by so many, including staff and executive leadership at East Los Angeles Community Corporation, to preserve the cultural legacy of Boyle Heights while creating affordable housing stock. The book, as a result, posits the well-supported theory that mariachi and Los Angeles are lassoed together as much as the country of Mexico and the regal musical form that has come to define all things Mexican are bound.

In the process, Catherine López Kurland uncovers her family history, it’s connection to the birth of Los Angeles as a city and the de-Mexicanization of her past as a result of a belief that being a descendant of Spanish “Californios” was somehow superior to status as a person of mixed indigenous and African heritage. Imagine the surprise and shock among the families who claim roots among the early settlers when they realized that the original “Angelenos” were mulattoes and mestizos.

In her essay tracing the rise, eventual decline and then the Phoenix-like resurrection of the Boyle Hotel, Kurland does not gloss over the fictional fantasy created in the homes of her forebears. In that family revision of actual history, a gallant, horseback “caballero,” sailed all the way around the tip of Argentina, up the Pacific and into the Los Angeles River Basin directly from Spain. The simple truth was that on one side of her family tree were landed Mexican homesteaders and on the other were Anglo settlers who married into Mexican families as much for convenience as for love.

It was one such union that resulted in the partitioning of the land around and below the “White Bluffs,” or as it was known then, “El Paredón Blanco.” This led to the development of the Boyle Heights that we have all come to know and love, the Boyle Heights we see around us today.

And had it not been for the marriage between Sacramenta López and George Cummings, an entrepreneur from Croatia who followed the Gold Rush to San Francisco—and with his earnings as a farmer who fed and supplied the miners, was able to purchase ranch land near Tehachapi—the Boyle Hotel and Boyle Heights might never have been built.

Kurland writes with clear scholarship in a readable style. While emotionally close to the historic circumstances she has researched thoroughly, she does not shy away from a need to uncover the truth and thus establish a basis for her preservation efforts. The efforts, which—as Evangeline Ordaz-Molina so eloquently shares in her introduction—dovetailed nicely with a vision among leadership at ELACC, for the resuscitation of a landmark, the restoration of the architectural icon imbued with the identity of a neighborhood and profoundly rooted in the songs and the soul of mariachi.

A compliment to Kurland’s riveting family history and the poetically erudite essay be Enrique Lamadrid which covers the history, the mechanics and lyrical truth inherent in mariachi music while illustrating the importance of the lesser known but no less important annual tribute to Santa Cecilia, Miguel Gandert delivers an array of modern-day musical saints with his honest, tender portraits. In page after page of indelible images, Gandert has absorbed the heart of mariachi and the psyche of a people.

The photographs alone would be enough to make this volume an important addition to anyone’s library. His photos are not mere sociological or anthropological studies. Each frame speaks to a conversation held off camera. The mariachi musicians are instantaneously welcomed as family. One gets the sense that Gandert has spoken to each of them and won them over. Their expressions are honest, never posed. They have allowed themselves to relax completely and display no self-consciousness. It is a thing of rare beauty indeed, much like the restoration of the Boyle or “Mariachi” Hotel.

Comments

Post a Comment